Scott

At some point -- dates were hazy by then -- Wilson decided to turn the Crozier party for home. Their tent had blown away on the 22nd, and the day after that the canvas roof and door of their igloo were ripped off by a blizzard, leaving the three men to lie in their bags in the open igloo, buried in snow. After forty-eight hours, they got up to make a meal of pemmican and tea, and during a lull in the blizzard, Bowers went out and found the tent on the slope below, folded up on itself like an umbrella. "Our lives had been taken away and given back to us," Cherry wrote simply. "We were so thankful we said nothing." [1]

Notes:

[1] Apsley Cherry-Garrard, The Worst Journey in the World, ch.VII.

July 25, 2011

July 22, 2011

Saturday, 22 July 1911

Amundsen

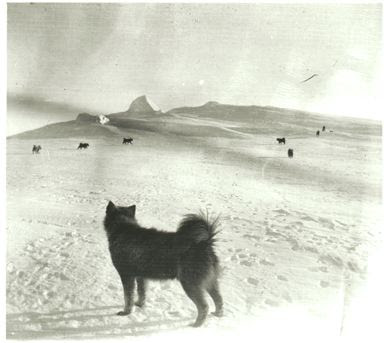

The dogs, Johansen wrote, "poor devils, enjoy life as much as they can in the cold and the dark, they have food enough, eat, sleep, have their amorous adventures when the bitches are on heat; but the pups who have lately come into the world soon succumbed to a relentlessly grim nature, and happy they are, I think, who escape the little enviable life of a sledge dog -- for no animal can have a worse life than the sledge dog." [2]

Notes:

[1] Roald Amundsen Bildearkiv, Nasjonalbiblioteket.

[2] Hjalmar Johansen, diary, 23 July, 1911, quoted by Roland Huntford in Scott and Amundsen (New York : Putnam, 1980, c1979), p.387-388.

The dogs, Johansen wrote, "poor devils, enjoy life as much as they can in the cold and the dark, they have food enough, eat, sleep, have their amorous adventures when the bitches are on heat; but the pups who have lately come into the world soon succumbed to a relentlessly grim nature, and happy they are, I think, who escape the little enviable life of a sledge dog -- for no animal can have a worse life than the sledge dog." [2]

Notes:

[1] Roald Amundsen Bildearkiv, Nasjonalbiblioteket.

[2] Hjalmar Johansen, diary, 23 July, 1911, quoted by Roland Huntford in Scott and Amundsen (New York : Putnam, 1980, c1979), p.387-388.

July 19, 2011

Wednesday, 19 July 1911

Amundsen

Work was finished on the sledges. Bjaaland's light-weight models weighed 24 kilos (35 lbs.), compared to the Fram's rebuilt sledges' 35 and (77 lbs.) Hagen's 75 kilos (165 lbs.). He had also prepared two pairs of skis for each man, one for the journey and a spare.

Work was finished on the sledges. Bjaaland's light-weight models weighed 24 kilos (35 lbs.), compared to the Fram's rebuilt sledges' 35 and (77 lbs.) Hagen's 75 kilos (165 lbs.). He had also prepared two pairs of skis for each man, one for the journey and a spare.

July 15, 2011

Saturday, 15 July 1911

Scott

At Cape Evans, Gran wrote, "One day passes very much like the next. After breakfast, Evans goes to his cartography, Scott to his diary, Day to his 'make and mend' [with the motor sledges], Meares to his harness-making, Oates (at 12) to his horses, Ponting to his photographic plates, Deb to his rock specimens, Taylor and I to our geographical studies or to our diaries. At noon Atkinson with Taylor or Ponting go up to The Ramp. Then comes lunch with cocoa, coffee, cheese, marmalade and honey. The afternoon is like the morning, except that after five o'clock the pianola starts up. Day, Ponting, and Atkinson are the main players, supplemented occasionally by Deb and Meares. Then comes supper. Taylor waits impatiently for the pudding. Finally it comes and the meal ends with the lighting-up of cigars and pipes. Atkinson or I put the gramophone on. Then we play dominoes or chess until ten. Nelson is the chess champion. About ten we begin to turn in; we read in bed, some till nearly midnight, and Deb, Nelson, and Ponting often later. Deb is the worst. Out go the lights at 11 and on goes the night watchkeeper's lamp. At midnight and at 4 a.m. readings of the barometer and thermometer are taken. Naturally the watcher is on the look-out every hour for signs of the aurora." [1]

Wilson, Cherry, and Bowers arrived at Cape Crozier on the far side of Ross Island, sixty miles (97 km) from Cape Evans. Temperatures had ranged from -40 °F (-40 °C) to -77.5 °F (-60.8 °C), with winds anywhere from Force 3 to Force 10 during a blizzard.

"The horror of the nineteen days it took us to travel from Cape Evans to Cape Crozier would have to be re-experienced to be appreciated," wrote Cherry later, "and any one would be a fool who went again: it is not possible to describe it. The weeks which followed them were comparative bliss, not because later our conditions were better -- they were far worse -- because we were callous. I for one had come to that point of suffering at which I did not really care if only I could die without much pain." [2]

They began almost at once to build a stone igloo in which they planned to shelter while collecting their penguin specimens. Cherry stopped keeping his diary, because his breath froze a film of ice on the paper, making it impossible to write on.

Notes:

[1] Tryggve Gran, diary, 15 July, 1911, quoted in The Norwegian With Scott : Tryggve Gran's Antarctic Diary 1910-1913 ([Greenwich] : National Maritime Museum, 1984), p.110.

[2] Apsley Cherry-Garrard, The Worst Journey in the World, ch.VII.

At Cape Evans, Gran wrote, "One day passes very much like the next. After breakfast, Evans goes to his cartography, Scott to his diary, Day to his 'make and mend' [with the motor sledges], Meares to his harness-making, Oates (at 12) to his horses, Ponting to his photographic plates, Deb to his rock specimens, Taylor and I to our geographical studies or to our diaries. At noon Atkinson with Taylor or Ponting go up to The Ramp. Then comes lunch with cocoa, coffee, cheese, marmalade and honey. The afternoon is like the morning, except that after five o'clock the pianola starts up. Day, Ponting, and Atkinson are the main players, supplemented occasionally by Deb and Meares. Then comes supper. Taylor waits impatiently for the pudding. Finally it comes and the meal ends with the lighting-up of cigars and pipes. Atkinson or I put the gramophone on. Then we play dominoes or chess until ten. Nelson is the chess champion. About ten we begin to turn in; we read in bed, some till nearly midnight, and Deb, Nelson, and Ponting often later. Deb is the worst. Out go the lights at 11 and on goes the night watchkeeper's lamp. At midnight and at 4 a.m. readings of the barometer and thermometer are taken. Naturally the watcher is on the look-out every hour for signs of the aurora." [1]

Wilson, Cherry, and Bowers arrived at Cape Crozier on the far side of Ross Island, sixty miles (97 km) from Cape Evans. Temperatures had ranged from -40 °F (-40 °C) to -77.5 °F (-60.8 °C), with winds anywhere from Force 3 to Force 10 during a blizzard.

"The horror of the nineteen days it took us to travel from Cape Evans to Cape Crozier would have to be re-experienced to be appreciated," wrote Cherry later, "and any one would be a fool who went again: it is not possible to describe it. The weeks which followed them were comparative bliss, not because later our conditions were better -- they were far worse -- because we were callous. I for one had come to that point of suffering at which I did not really care if only I could die without much pain." [2]

They began almost at once to build a stone igloo in which they planned to shelter while collecting their penguin specimens. Cherry stopped keeping his diary, because his breath froze a film of ice on the paper, making it impossible to write on.

Notes:

[1] Tryggve Gran, diary, 15 July, 1911, quoted in The Norwegian With Scott : Tryggve Gran's Antarctic Diary 1910-1913 ([Greenwich] : National Maritime Museum, 1984), p.110.

[2] Apsley Cherry-Garrard, The Worst Journey in the World, ch.VII.

July 13, 2011

Thursday, 13 July 1911

Amundsen

"Everyone," Amundsen wrote in his diary, "will have two pairs of ski. On the first pair, intended for daily use during the polar journey -- fixed bindings [in one piece] will be used -- the original Huitfeldt bindings. On the other -- to be taken as a spare pair -- Bjaaland is making binding ears in two parts, so that they can be mounted during the journey, if necessary. The point it, it will take too much space to have the bindings attached." [2]

Notes:

[1] Roald Amundsen Bildearkiv, Nasjonalbiblioteket.

[2] Roald Amundsen, diary, [14? July, 1911], quoted by Roland Huntford in The Amundsen Photographs (London : Hodder & Stoughton, c1987), p.112.

"Everyone," Amundsen wrote in his diary, "will have two pairs of ski. On the first pair, intended for daily use during the polar journey -- fixed bindings [in one piece] will be used -- the original Huitfeldt bindings. On the other -- to be taken as a spare pair -- Bjaaland is making binding ears in two parts, so that they can be mounted during the journey, if necessary. The point it, it will take too much space to have the bindings attached." [2]

Notes:

[1] Roald Amundsen Bildearkiv, Nasjonalbiblioteket.

[2] Roald Amundsen, diary, [14? July, 1911], quoted by Roland Huntford in The Amundsen Photographs (London : Hodder & Stoughton, c1987), p.112.

July 10, 2011

Monday, 10 July 1911

Amundsen

With the approaching spring and the easing-up of work, Amundsen had time to think, and he thought of the English. He dwelt at length in his diary on Shackleton. "Either the Englishmen [on Shackleton's expedition] must have had bad dogs or -- they didn't know how to use them." [2]

"Then comes S's reference [in The Heart of the Antarctic] to fur clothes. Furs are not necessary, he opines, [because they were not used] on Discovery or Nimrod. That is enough to prove that furs are unnecessary. Very possibly so. But [then why] does S. complain so often about the cold on his long Southern journey?... One thing I think I can ... say, if Shackleton had been equipped in a practical manner; dogs, fur clothes and, above all, skis ... and, naturally understood their use ... well then, the South Pole would have been a closed chapter. I admire in the highest degree what he and his companions achieved with the equipment they had. Bravery, determination, strength they did not lack. A little more experience -- preferably a journey in the far worse conditions in the Arctic ice -- would have crowned their work with success."

"The English have loudly and openly told the world that skis and dogs are unusable in these regions and that fur clothes are rubbish. We will see -- we will see. I don't want to boast -- it's not exactly in my line, but when people decide to attack the methods which have brought the Norwegians into the leader class as polar explorers -- skis and dogs, well, then, one must be allowed to be irritated and try to show the world that it is not only luck that brought us through with the help of such means, but calculation and understanding of how to use them."

Notes:

[1] Roald Amundsen Bildearkiv, Nasjonalbiblioteket.

[2] Roald Amundsen, diary, 11 July, 1911, quoted by Roland Huntford in Scott and Amundsen (New York : Putnam, 1980, c1979), p.392.

With the approaching spring and the easing-up of work, Amundsen had time to think, and he thought of the English. He dwelt at length in his diary on Shackleton. "Either the Englishmen [on Shackleton's expedition] must have had bad dogs or -- they didn't know how to use them." [2]

"Then comes S's reference [in The Heart of the Antarctic] to fur clothes. Furs are not necessary, he opines, [because they were not used] on Discovery or Nimrod. That is enough to prove that furs are unnecessary. Very possibly so. But [then why] does S. complain so often about the cold on his long Southern journey?... One thing I think I can ... say, if Shackleton had been equipped in a practical manner; dogs, fur clothes and, above all, skis ... and, naturally understood their use ... well then, the South Pole would have been a closed chapter. I admire in the highest degree what he and his companions achieved with the equipment they had. Bravery, determination, strength they did not lack. A little more experience -- preferably a journey in the far worse conditions in the Arctic ice -- would have crowned their work with success."

"The English have loudly and openly told the world that skis and dogs are unusable in these regions and that fur clothes are rubbish. We will see -- we will see. I don't want to boast -- it's not exactly in my line, but when people decide to attack the methods which have brought the Norwegians into the leader class as polar explorers -- skis and dogs, well, then, one must be allowed to be irritated and try to show the world that it is not only luck that brought us through with the help of such means, but calculation and understanding of how to use them."

Notes:

[1] Roald Amundsen Bildearkiv, Nasjonalbiblioteket.

[2] Roald Amundsen, diary, 11 July, 1911, quoted by Roland Huntford in Scott and Amundsen (New York : Putnam, 1980, c1979), p.392.

July 7, 2011

Winter 1911

Amundsen

At some point during the winter at Framheim, the men took the time to be photographed in their polar gear. The reindeer-skin clothing was not made to measure, and so each man adapted his to suit himself.

Notes:

[1] Roald Amundsen Bildearkiv, Nasjonalbiblioteket.

[2] Roald Amundsen Bildearkiv, Nasjonalbiblioteket.

[3] Roald Amundsen Bildearkiv, Nasjonalbiblioteket.

[4] Roald Amundsen Bildearkiv, Nasjonalbiblioteket.

[5] Roald Amundsen Bildearkiv, Nasjonalbiblioteket.

[6] Roald Amundsen Bildearkiv, Nasjonalbiblioteket.

[7] Roald Amundsen Bildearkiv, Nasjonalbiblioteket.

At some point during the winter at Framheim, the men took the time to be photographed in their polar gear. The reindeer-skin clothing was not made to measure, and so each man adapted his to suit himself.

Notes:

[1] Roald Amundsen Bildearkiv, Nasjonalbiblioteket.

[2] Roald Amundsen Bildearkiv, Nasjonalbiblioteket.

[3] Roald Amundsen Bildearkiv, Nasjonalbiblioteket.

[4] Roald Amundsen Bildearkiv, Nasjonalbiblioteket.

[5] Roald Amundsen Bildearkiv, Nasjonalbiblioteket.

[6] Roald Amundsen Bildearkiv, Nasjonalbiblioteket.

[7] Roald Amundsen Bildearkiv, Nasjonalbiblioteket.

Labels:

Bjaaland,

Hassel,

Helmer Hanssen,

Johansen,

Norwegian equipment,

Prestrud,

Stubberud,

Wisting

July 5, 2011

Wednesday, 5 July 1911

Scott

The Cape Crozier party had begun relaying, taking one sledge at a time and going back for the other, making them travel three miles for every one of distance. On the 5th, they managed only one and a half miles in soft new snow and a strong breeze, and recorded a noon temperature of almost -77°. "The day lives in my memory," wrote Cherry, "as that on which I found out that records are not worth making." [1] Wilson apologised continually, saying that he had never dreamed it would be so bad.

Notes:

[1] Apsley Cherry-Garrard, The Worst Journey in the World, ch.VII.

The Cape Crozier party had begun relaying, taking one sledge at a time and going back for the other, making them travel three miles for every one of distance. On the 5th, they managed only one and a half miles in soft new snow and a strong breeze, and recorded a noon temperature of almost -77°. "The day lives in my memory," wrote Cherry, "as that on which I found out that records are not worth making." [1] Wilson apologised continually, saying that he had never dreamed it would be so bad.

Notes:

[1] Apsley Cherry-Garrard, The Worst Journey in the World, ch.VII.

July 4, 2011

July 1911

Amundsen

On 4th July, Amundsen presented his "improved plan" for the attack on the Pole. They would start in the middle of September, instead of 1st November as originally planned, all eight men taking eighty-four dogs to the depot at 83°. They would build igloos and wait there until the middle of October, when the midnight sun would return, and then set off for the Pole.

A few weeks later, towards the end of the month, he revised this, suggesting a preliminary trip into King Edward VII Land to test equipment. He put this to the vote and was twice voted down, accepted the result, and proposed heading straight for the Pole on 24 August.

"The thought of the English gave him no peace," Hassel wrote later. "For if we were not first at the Pole, we might just as well stay home." [1]

Sources:

[1] Sverre Hassel, diary, 13 August, 1911, quoted by Roland Huntford in Scott and Amundsen (New York : Putnam, 1980, c1979), p.393.

On 4th July, Amundsen presented his "improved plan" for the attack on the Pole. They would start in the middle of September, instead of 1st November as originally planned, all eight men taking eighty-four dogs to the depot at 83°. They would build igloos and wait there until the middle of October, when the midnight sun would return, and then set off for the Pole.

A few weeks later, towards the end of the month, he revised this, suggesting a preliminary trip into King Edward VII Land to test equipment. He put this to the vote and was twice voted down, accepted the result, and proposed heading straight for the Pole on 24 August.

"The thought of the English gave him no peace," Hassel wrote later. "For if we were not first at the Pole, we might just as well stay home." [1]

Sources:

[1] Sverre Hassel, diary, 13 August, 1911, quoted by Roland Huntford in Scott and Amundsen (New York : Putnam, 1980, c1979), p.393.

Tuesday, 4 July 1911

Amundsen

Wisting, Amundsen wrote in his diary, "is sitting in the Great Ice Barrier and sewing tents on his Singer -- in +14°. To stop water dripping, he has lined his snowy sewing room with blankets ... and these insulate extraordinarily well. The sewing machine is a little sleepy first thing in the morning, but later on works well.... He is sewing new, light groundsheets in [the tents]. By this means, we will save several kilos." [2]

"Our sledging tents are of thin, white cloth, and that will be no good in the spring, when the sun is high. It will then be preferable to have a dark tent, into which one can go after the day's work, and rest one's eyes. Another consideration is that a dark colour will absorb the sun's rays to a greater degree, and make the tent warm. Ah well, we rarely allow ourselves to be defeated. We have made a mixture of ink powder and black boot polish, and with that product, we will get our tents as dark as we want."

Notes:

[1] Roald Amundsen Bildearkiv, Nasjonalbiblioteket.

[2] Roald Amundsen, diary, 5 July, 1911, quoted by Roland Huntford in The Amundsen Photographs (London : Hodder & Stoughton, c1987), p.111.

Wisting, Amundsen wrote in his diary, "is sitting in the Great Ice Barrier and sewing tents on his Singer -- in +14°. To stop water dripping, he has lined his snowy sewing room with blankets ... and these insulate extraordinarily well. The sewing machine is a little sleepy first thing in the morning, but later on works well.... He is sewing new, light groundsheets in [the tents]. By this means, we will save several kilos." [2]

"Our sledging tents are of thin, white cloth, and that will be no good in the spring, when the sun is high. It will then be preferable to have a dark tent, into which one can go after the day's work, and rest one's eyes. Another consideration is that a dark colour will absorb the sun's rays to a greater degree, and make the tent warm. Ah well, we rarely allow ourselves to be defeated. We have made a mixture of ink powder and black boot polish, and with that product, we will get our tents as dark as we want."

Notes:

[1] Roald Amundsen Bildearkiv, Nasjonalbiblioteket.

[2] Roald Amundsen, diary, 5 July, 1911, quoted by Roland Huntford in The Amundsen Photographs (London : Hodder & Stoughton, c1987), p.111.

July 2, 2011

Sunday, 2 July 1911

Amundsen

The Aurora Australis over the South Pole. Photo by Keith Vanderlinde / National Science Foundation. [1]

The Aurora Australis over the South Pole. Photo by Keith Vanderlinde / National Science Foundation. [1]

The aurora, Amundsen wrote, stretched "in mighty curtains .... It was a lovely sight. It was as if in its light and power it wanted to fight a battle with the dawn over who would be first. In giant folds it thrust forwards, withdrew again and once more forced itself forwards -- shining in bright green, yellow & red. But, although its attack was violent, it had to give way to the dawn that slowly but surely was working its way up." [2]

"Sun, oh Sun, Thou art on the way back to us again, and a boundless welcome shalt Thou have. He first learns to treasure Thy blessed powers who once has been deprived of them. Life Thou givest; health and wellbeing."

The first part of the winter "has passed in a flash. Time has fled, but the memories are made .... [It] may seem odd but ... it is certain that not one of us have any doubts that we shall get through. There are no 'buts' to be heard. The matter seems decided. And so it ought to be. A lot will have to come in our way to deprive us from our goal. May the Almighty God be with us!" [3]

Notes:

[1] National Science Foundation, Office of Polar Programs.

[2] Roald Amundsen, diary, 3 July, 1911, quoted by Roland Huntford in Scott and Amundsen (New York : Putnam, 1980, c1979), p.381.

[3] Roald Amundsen, diary, 3 July, 1911, quoted by Roland Huntford in Scott and Amundsen (New York : Putnam, 1980, c1979), p.391.

The Aurora Australis over the South Pole. Photo by Keith Vanderlinde / National Science Foundation. [1]

The Aurora Australis over the South Pole. Photo by Keith Vanderlinde / National Science Foundation. [1]The aurora, Amundsen wrote, stretched "in mighty curtains .... It was a lovely sight. It was as if in its light and power it wanted to fight a battle with the dawn over who would be first. In giant folds it thrust forwards, withdrew again and once more forced itself forwards -- shining in bright green, yellow & red. But, although its attack was violent, it had to give way to the dawn that slowly but surely was working its way up." [2]

"Sun, oh Sun, Thou art on the way back to us again, and a boundless welcome shalt Thou have. He first learns to treasure Thy blessed powers who once has been deprived of them. Life Thou givest; health and wellbeing."

The first part of the winter "has passed in a flash. Time has fled, but the memories are made .... [It] may seem odd but ... it is certain that not one of us have any doubts that we shall get through. There are no 'buts' to be heard. The matter seems decided. And so it ought to be. A lot will have to come in our way to deprive us from our goal. May the Almighty God be with us!" [3]

Notes:

[1] National Science Foundation, Office of Polar Programs.

[2] Roald Amundsen, diary, 3 July, 1911, quoted by Roland Huntford in Scott and Amundsen (New York : Putnam, 1980, c1979), p.381.

[3] Roald Amundsen, diary, 3 July, 1911, quoted by Roland Huntford in Scott and Amundsen (New York : Putnam, 1980, c1979), p.391.

July 1, 2011

Saturday, 1 July 1911

Scott

Cherry wrote later, "During these days the blisters on my fingers were very painful. Long before my hands were frost-bitten, or indeed anything but cold, which was of course a normal thing, the matter inside these big blisters, which rose all down my fingers with only a skin between them, was frozen into ice. To handle the cooking gear or the food bags was agony; to start the primus was worse; and when, one day, I was able to prick six or seven of the blisters after supper and let the liquid matter out, the relief was very great. Every night after that I treated such others as were ready in the same way until they gradually disappeared. Sometimes it was difficult not to howl." [2]

Blistering is in fact a symptom of relatively shallow frostbite, deeper than when the skin becomes numb and white, but not as bad as when the affected area turns hard and, in worst cases, black.

Notes:

[1] Scott Polar Research Institute.

[2] Apsley Cherry-Garrard, The Worst Journey in the World, ch.VII.

Cherry wrote later, "During these days the blisters on my fingers were very painful. Long before my hands were frost-bitten, or indeed anything but cold, which was of course a normal thing, the matter inside these big blisters, which rose all down my fingers with only a skin between them, was frozen into ice. To handle the cooking gear or the food bags was agony; to start the primus was worse; and when, one day, I was able to prick six or seven of the blisters after supper and let the liquid matter out, the relief was very great. Every night after that I treated such others as were ready in the same way until they gradually disappeared. Sometimes it was difficult not to howl." [2]

Blistering is in fact a symptom of relatively shallow frostbite, deeper than when the skin becomes numb and white, but not as bad as when the affected area turns hard and, in worst cases, black.

Notes:

[1] Scott Polar Research Institute.

[2] Apsley Cherry-Garrard, The Worst Journey in the World, ch.VII.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)